Timeline

1939 Low's Calculators Ltd incorporated at 180 Tottenham Court Road

1961 Systemation Ltd incorporated with Bill Gannon as MD

1962 Low's Calculators Ltd becomes Business Mechanisation Ltd with Bill Heselton as MD

1962 Systemation's BETSIE launched

1963 Systemation's SADIE launched at Business Efficiency Exhibition, Olympia

1964 Business Mechanisation Ltd becomes Bismec Ltd and later Bismec Group Ltd. A joint production and marketing deal between Systemation Ltd and Bismec Ltd

1969 Systemation and Business Mechanisation Ltd together incorporate Business Computers Ltd

1969 Systemation and Business Mechanisation Ltd together incorporate Business Computers Ltd

1969 Business Computers Ltd in Public Share offering - 700,000 ordinary 2/- shares for sale at 21/- each - oversubscribed by 40%

1970 SUSIE launched

1971 BCL acquires a 40% share of Société Machines d'Organisation BCL SA - their Belgium distributor

1971 Molecular 18 Mark One launched

1971 First M18 installation at Thames Electric Co., Surrey

1972 BCL agreement with German Company Kämmerei Döhren AG, Hanover

1974 Business Computers Ltd in receivership

BCL’s origins can be traced back to three earlier companies:

- Unex Ltd. (established in the late 1930s)

- Low's Calculators (1939)

- Systemation Ltd. (1961).

Jewish refugees from continental Europe founded Unex in the late 1930s. They established a business selling and maintaining accounting machines - mainly those manufactured by Burroughs. After the war ended, they also had a reseller agreement with the German company Continental Wanderer, who manufactured electro-mechanical accounting machines. One of their biggest customers was Barclays Bank who used the ‘Continental Class 900’ machine extensively.

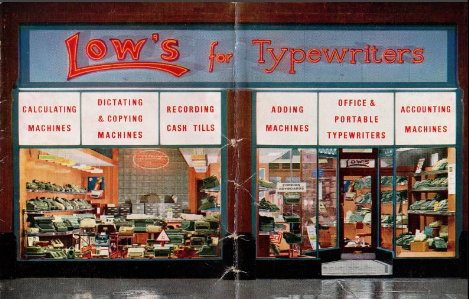

On 11th Dec 1939, Unex was bought by Mr Thomas Low and re-incorporated as Low's Calculators Ltd., which went on to operate out of Unex’s premises at 15 Holborn Viaduct, London EC2. In 1962, Low's Calculators changed its name to Business Mechanisation Ltd. and moved to 180 Tottenham Court Road, London, although the name above the new shop stayed as Lows for quite some time.

At the Business Efficiency Exhibition (BEE) in Olympia, London, 1963, Business Mechanisation exhibited an electro-mechanical invoicing machine built from an Adler electric typewriter and a Walther decimal printing calculator. Attending the exhibition, Bill Gannon and Gordon Clark from Systemation Ltd. took the opportunity to describe to Business Mechanisation a purely electronic system they had designed that would perform a similar job more reliably and certainly faster. It was agreed that Systemation’s new machine would be demonstrated to Bill Hesleton and Steve Brady from Business Mechanisation as soon as it was complete. This occurred several months later and Business Mechanisation cancelled development of their own product that they realised was already out of date. Business Mechanisation agreed to take over the marketing of the new electronic machine and immediately ordered twenty systems.

Systemation was formed in Hove, Sussex in 1961 by a group of six engineers who had worked previously in the aircraft industry. They quickly produced an electronic calculator called BETSIE that operated in Pounds Sterling and was designed to calculate betting shop winnings. BETSIE sold well throughout the UK, and this encouraged the team to build increasingly sophisticated machines for new markets.

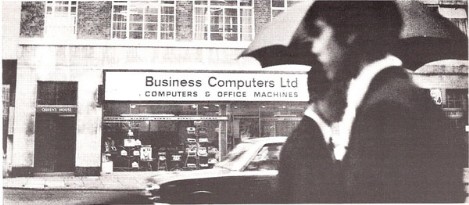

Business Mechanisation Ltd became the sole agent for all of Systemation’s products in 1965 and sold over 85 systems in the first year. Business Mechanisation Ltd changed its name to BisMec Group Ltd. in 1968, and a year later acquired all of Systemation’s assets and formed the new company Business Computers Ltd - or BCL as they were then always known.

Each of the two original companies had specific strengths and very little overlap in abilities. To benefit from this, all sales and marketing was conducted from Tottenham Court Road and was led by Bill Heselton and the BisMec team while Bill Gannon and the Systemation team managed all the technical development and programming from Portslade. While this sounds like two companies working quite separately, there was a constant dialog between the two offices.

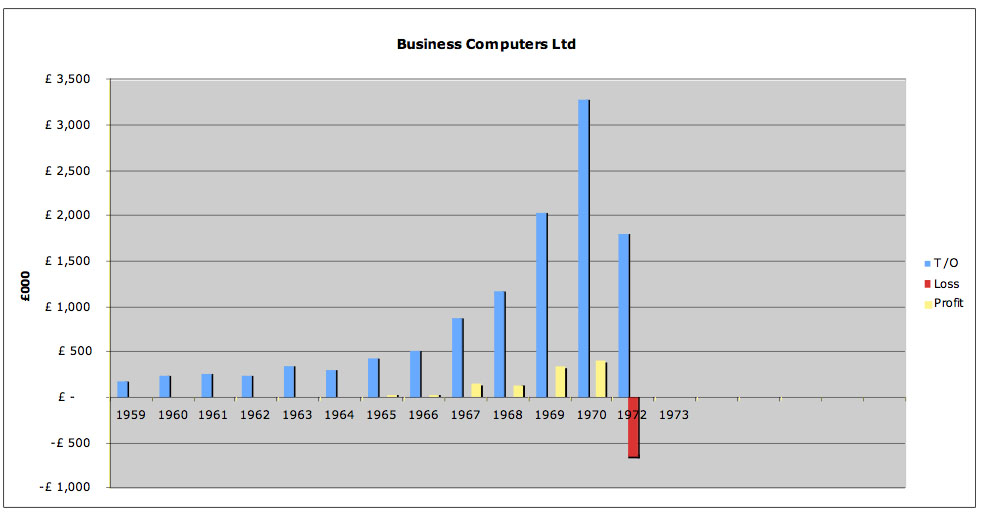

Spectacular Growth

By 1967, the group had opened 13 sales offices throughout the UK and the Republic of Ireland and had sold over 700 systems. Two years later six more sales offices had been added. SADIE and SUSIE systems typically sold for between £2,750 and £6,750 and SUSIE systems between £7,000 and £30,000. Later in 1969, Bill Gannon described the early says of BCL saying ‘There was virtually no competition for this type of machine when we started serious production. By the time it arrived in the field we were off to a flying start with 60-70 machines already out.’

BCL offered shares to the public in 1969 by issuing 700,000 ordinary 2/- shares at 21/- each which represented some 40% of the equity. The Times reported that this represented a price-to-earnings ratio of 15.9, dividends were expected at 40%, and that it expected an enthusiastic response. The share issue was over-subscribed by 40% - a record at the time.

Multi-SUSIE was launched in 1969 at the Business Efficiency Exhibition that year. Individual SUSIE workstations could now be connected to a central machine with a larger drum store that acted as the common program and data store for each SUSIE user. The new multi-user system proved to be very successful commercially with over 300 systems sold by 1972.

The Molecular 18

In October 1971, again at the Business Efficiency Exhibition, BCL launched its latest machine, a general-purpose mini-computer known as the Molecular 18. This was described ‘as the most interesting exhibit … the new Molecular 18 system attracted a lot of attention’. The machine shown at the exhibition was destined for Unigate – one of BCL’s first customers for the machine. BCL reported sales of over sixty Molecular systems within six months of the launch at BEE.

BCL sold the Molecular with just the basic operating software. Customers were expected to develop their own systems and, for their initial customers, this was perfectly acceptable. BCL produced a very basic assembler but no high level programming languages that would make producing applications easier. Other mini-computer manufacturers in the UK and elsewhere produced machines similar to the Molecular but devoted resources in producing system software such as assemblers, high-level languages and report generators. Many of these other companies also produced a range of software-compatible machines allowing existing customers to upgrade as their use of the system grew. A typical BCL customer at the time was Legal and General Insurance who chose the Molecular 18 after looking carefully at other UK and international suppliers. They had an established IT department, employed programmers and managed all their own system development.

BCL reported a loss of £232,000 for the first half of 1971. Orders for the Molecular 18 continued to grow, however, and BCL’s management were optimistic that the business would soon be profitable once again. Mr Lewis Harris, Managing Director of BCL, told Computer Weekly that ‘orders for Molecular 18 were exceptionally good and far greater than at earlier launches of SADIE, SUSIE and Multi-SUSIE’.

By late 1972, BCL realised that it was not going to be able to keep up with rival mini-computer manufacturers, as they could not afford the resources to develop the advanced systems software or the range of machines that was expected. Instead, they decided to operate as they had when selling SADIE and SUSIE systems and develop application software, using their basic software tools, specifically for UK businesses that were not interested in running their own development programme, but rather wanted to buy a ready-built business solution instead. BCL changed its marketing of the Molecular 18 to promote complete business solutions with application software included, albeit without appreciating the amount of effort that would subsequently be required.

Increasing losses and cash-flow problems

BCL grew very rapidly with sales offices opening around the UK and abroad and employing over 590 people at its peak. However, the management of BCL had hugely under-estimated the complexity of producing complete systems including application software, and their experience with SADIE and SUSIE did not scale well up to the multi-user application systems expected by customers of the Molecular 18. The rapid growth inevitably caused severe cash-flow problems and increasing losses and by January 1974, BCL’s share price dropped by almost 80% to just 17p per share.

Limited financial help came in January 1974 from the German Company Kämmerei Döhren AG of Hanover when they bought three million new shares in BCL for £600,000, a transaction that bought them 40% of the total equity of the company. The German company also had the option to buy further shares to increase their holding to 49%. Kämmerei Döhren (KD) was not itself involved in computer manufacture, but was the major shareholder in a computer manufacturer called Wagner Computer Vertrieb GmbH that produced a small system described as complementary to BCL’s Molecular. Lewis Harris, then MD of BCL expected there to be a common product within two years. Four months later, BCL reported that it had negotiated a further £200,000 loan with KD.

BCL’s chairman, Ronald Aitken , reported to Computer Weekly that there had been discussions between BCL and Department of Trade and Industry (DTI) but that BCL had made not made a formal approach to government to secure funding. BCL had made overtures to government before; in March 1972, it held a reception close to the House of Commons to demonstrate the Molecular 18 to members of parliament. It also gave the opportunity for BCL’s managing director, Lewis Harris, to remind those MPs attending that there ‘were other computer manufacturers in the UK besides ICL’. Harris also made the point that BCL was not looking for funding, but did think it ‘strange that BCL had never been invited to tender for government orders’. In an answer to a House of Commons question in June 1974 from Mr Eric Moon MP, Mr Anthony Wedgewood-Benn MP, Industry Secretary, replied that BCL did approach the DTI seeking financial support before the sale of shares to Kämmerei Döhren.

Bankruptcy

From the outset, Clydesdale Bank were proving funds in the form of loans and the overdraft facility required for the continued operation of BCL. As of June 1974, the bank held over £100M in secured loans to BCL and after a meeting in June 1974 that failed to negotiate further funding, Clydesdale Bank called in their loans and forced BCL into receivership. Trading in BCL’s shares was suspended immediately and a receiver was appointed by the bank.

At the time, Ronald Aitken, then chairman of BCL said ‘The immediate cause of the failure of the company was that we announced a further £200,000 loan from Kämmerei Döhren last month on the basis of telex messages and the money never came through.’ Dataweek reported in June 1974 that KD itself was under pressure in Germany and was currently being investigated by the Berlin Public Prosecutor in relation to allegations of fraud and mismanagement. This investigation was sparked off by a group of KD’s shareholders led by the ex-managing director of Wagner Computer, and led to suspension of KD share trading by the Hannover Stock exchange.

BCL went into receivership on 26th June 1974. Mr Ian Watt of Thomas McLintock, who was appointed as official receiver, told Computer Weekly ‘I am anxious to get it over to users not to rush off and make their own arrangements for systems support and maintenance’. The company had some 400 to 500 employees and they agreed to carry on for at least two weeks, which is all the time Mr Watt felt he had to rescue the company.

Just prior to this point, BCL’s management was expecting to complete a deal with another German company, Preuβler AG of Berlin, which was prepared to buy the rights to all the BCL expertise. This was expected to bring £8m into the business but Aitken told Computer Weekly that the deal was now unlikely to go through.

In an almost comically tragic statement in June 1974, Aitken told Computer Weekly: ‘The extent of Business Computer’s problems first became clear at the end of last year when I discovered that programming would cost a bomb more than we had budgeted for. We tried desperately to get things right and hired an army of programmers – at one time we were up to 750-800 people altogether and very vastly over-staffed with programmers.’